Home Saint Manuscripts

Since 2011 the research team of the IAE’s archive (Institute of Archeology and Ethnology, NAS RA) has conducted investigation of Armenian shrines, holy sanctuaries and places of worship.

A shrine is an area where the actual complex of worship is carried out, where people do various actions, recite or sing texts with specific context (prayers); and these actions and texts keep the connection between humans and the higher power. Within the worldview of local people a shrine is a source of holy power, a place where miracles happen, a place where their speech and actions reach the high recipient. If a shrine is also a pilgrimage site then the road reaching there is extremely important, as the journey itself is a ritual action and expresses a person’s respect and appreciation towards the object of worship.

Armenian shrines are an important and unique form of folk culture. Armenians have numerous functioning monasteries and churches, as well as humble local folk shrines: chapels or open-air areas. Folk sanctuaries are dedicated to patron saints who can fulfill the requests of pilgrims: bestow cures to the sick, preserve the health and lives of servicemen, gift a long-awaited child, find peace for the soul, help marry a person they love, etc. Saints contact the mortals through dreams, visions and powerful waves of emotions within the shrine or after visiting it. Places like these do not have permanent clergymen-servants, although in special cases ceremonies can take place in the presence of priests.

Armenian folk sanctuaries are characteristic only to the followers of the Armenian Holy Apostolic Church and Armenian Catholic Church.

Armenian folk Christianity is a rich branch of ethnic and national culture; and the shrine is its material expression. Folk shrines can be found in various locations in Armenia. Although they look different, the worship that takes place there has the same or similar expressions.

Usually, the folk sanctuaries have guardian-caretakers, who not only keep the cleanliness of the place and buy candles for the visitors of the sanctuary from the donations of the believers, but can perform some healing rituals in the name of the sanctuary’s patron saint.

One of the typical manifestations of Armenian Christianity is the ‘Home Saint’. The Home Saint is a sacred power that is present in or inhabits private houses or property that belongs to a family or a lineage. It can have or not have a materialistic expression, e.g. in form of an item. In some rural houses, a miracle can sometimes occur in a random corner of the property, for example, light or an image appears on a wall; the animals in the barn are constantly sweating despite the weather or are constantly uneasy. The Saint can appear in the visions of one or a few of the family’s members, for instance, when a child or an adult constantly report that a stranger, dressed in white or red, is walking on the property, although not everyone can see him/her. The Saint can appear in a dream of the family member and demand for a special corner or room to be decorated in his/her honor, a place where people can communicate with the spirit; or a separate chapel to be built. Such visions and dreams often gift the person experiencing them the ability of foresight or the ability to cure people suffering from illnesses with the help of prayers or rituals. The Saint appearing through dreams and visions can hint that a holy object is being kept in a specific place in the house. As a result, family members discover cross-stones, church items or codices within their houses.

Most often though the family comes in possession of an item that had been kept in a church or a monastery long ago. That item can be the heritage of a priest ancestor or an item that had an important religious meaning and which the family has vowed to guard as a result of war or other misfortunes. Usually such items or ‘movable sacred relics’ change their location when the family does. In hostile environments, the relics become small islands of national culture, whereas in peaceful and safe environments chapels and even churches are built on top of them.

These are the reasons why the Home Saints emerge. If they make many miracles happen, cure people, or help them find the fulfillment of dreams, then, with their popularity, the Saints can sometimes compete with monasteries. If the reliquary leaves the family for one reason or another, people expect misfortune. There have been cases when after the abduction of reliquaries families have perished and entire villages have been emptied by most of their inhabitants.

The culture of the Home Saints is still ongoing in numerous settlements of Armenia. People continue to visit ‘the Home of the Saint”, perceiving that action as a pilgrimage. In those small sanctuaries, the pilgrims light candles, pray, perform rituals, bring offerings, and sometimes even stay for the night in the sanctuary with the intention to receive a cure. Until today they are Home Saint sanctuaries where people with special powers, perform healing and protective rituals.

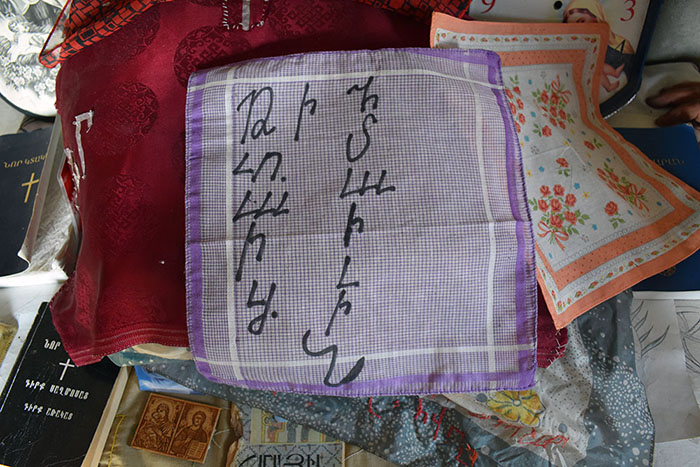

The Home Saints are distinctive with the fact that a large number of headscarves and large embroidered handkerchiefs are kept within them. The folk calls it ‘shushpa’. Most of the shushpas in a sanctuary are donations of the believers as a sign of veneration, the importance of the request or the fulfillment of their wishes by the patron-saint. A lot of shushpas are handmade objects which have specific texts written or sewn on them. These can be the name of the saint/shrine, expressions of gratitude or the fact that the object is a gift, sometimes the name of the donator or the name of the person for whom the donator is asking for a blessing.

However, the most important shushpas are the pieces of clothing that are used to wrap the primary holy object. These shushpas inherit the holiness of the object and require special treatment. Those are not to be used as a headscarf, a piece of decoration or clothing. They can only be washed without any soap in the wooden basin serving to make the dough of the bread or in bowls that have never been used before. Usually, the washer has to be a virgin girl, as having the right to touch a shushpa infers integrity, innocence and purity. Shushpas must not be thrown away, and if they frayed, they can only be burnt and the ashes must be buried under a tree or a place where people usually do not tread. That’s why shushpas that are used to wrap holy items are sometimes over 100 years old.

The Home Saint as a shrine can be inside a residential house, in a special, decorated corner, or in a separate room. It can also be a chapel in the land surrounding or near the house, and its doors are always open for pilgrims.

Inside a building, the relic is housed within a wardrobe or a special recess inside the wall, which plays the role of a unique altar.

The chapel does not have any specific design, its appearance depends on the financial capacity of the owner family. If the family has limited financial resources, the Home Saint can only have a small, modest house-chapel. On the other hand, rich families build churches and chapels designed by professional architects, and they often maintain the typical style of Armenian churches.

From the inside, the Home Saints are very much alike. Whether it’s a corner in the house, a room, or a beautiful church-like chapel, they all have a special place for lighting candles and are decorated with holy paintings (icons). Also, the donations of the believers such as shushpas, small embroidered cross-stones and wooden crosses are stored in them. There is often a small metallic bowl for monetary donations.

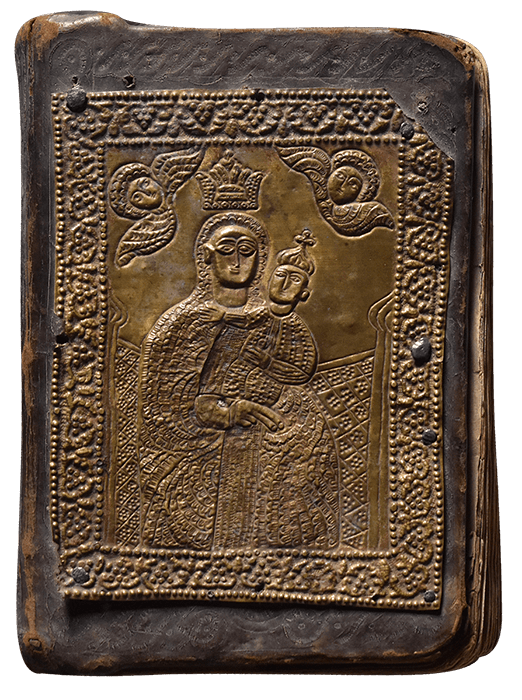

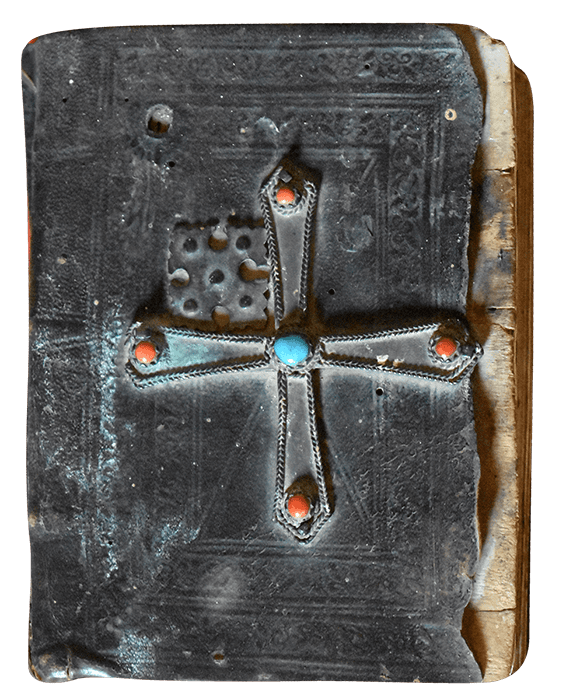

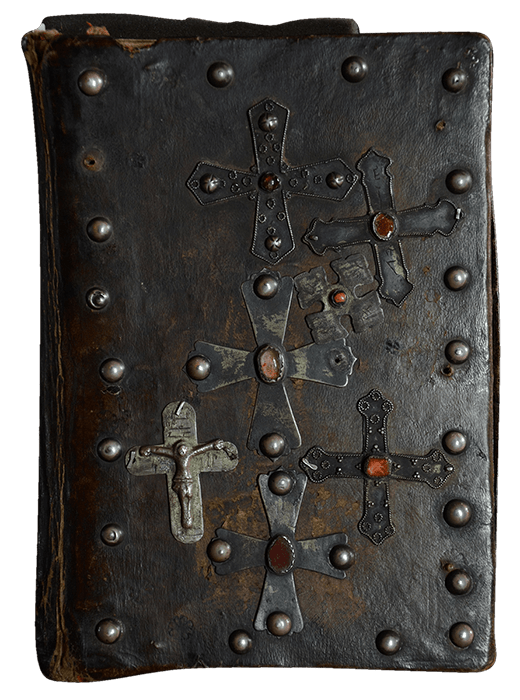

If the primary holy object is stored within the chapel of the Home Saint, then a special wooden box or chest is made to house it. Only in very rare cases is the holy object placed in an open uncovered state.

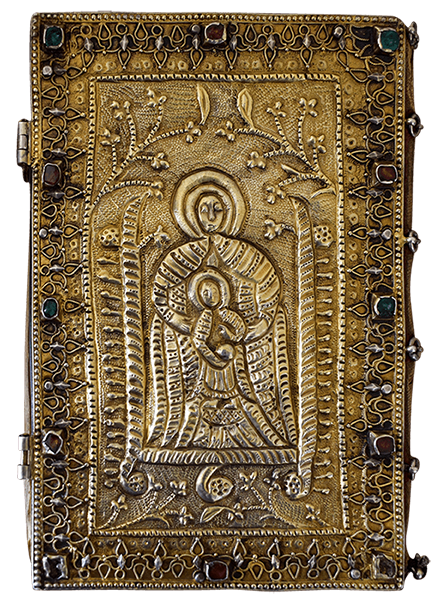

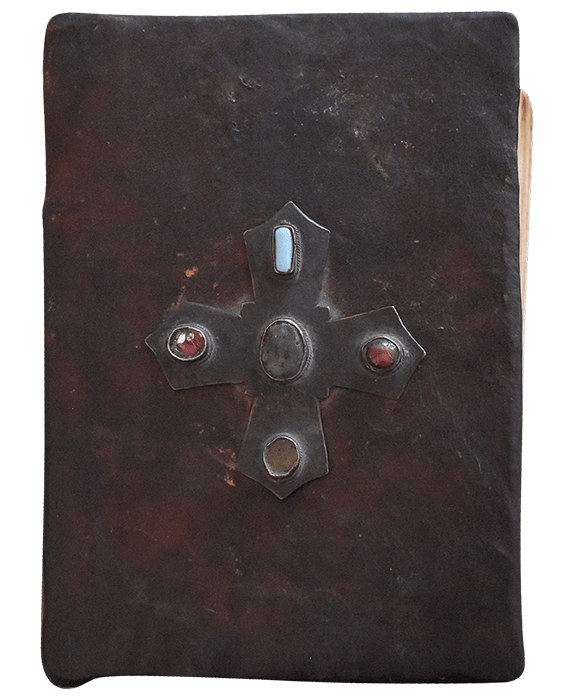

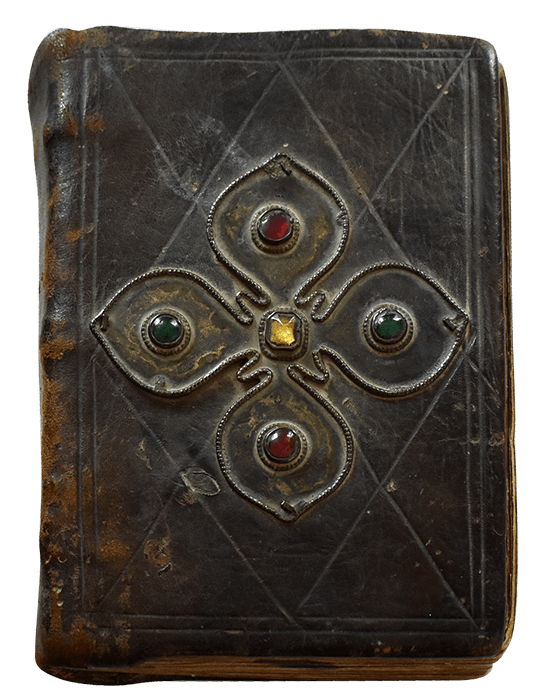

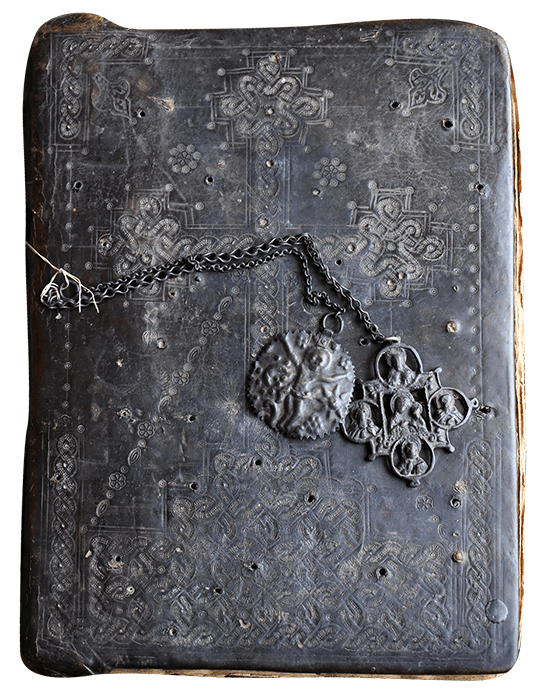

The holy objects of the Home Saint can be: a. Wonder-maker books, b. Relics and reliquaries, c. Crosses, d. Church utensils, pieces of garments of a priest, e. Items found in mysterious circumstances, statuettes brought from Jerusalem or Western Armenia, old coins, rings and chunks of rocks.

Through all of these items miracles and healing occur.

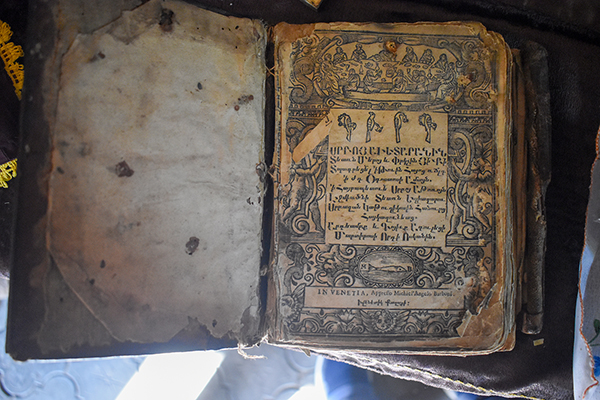

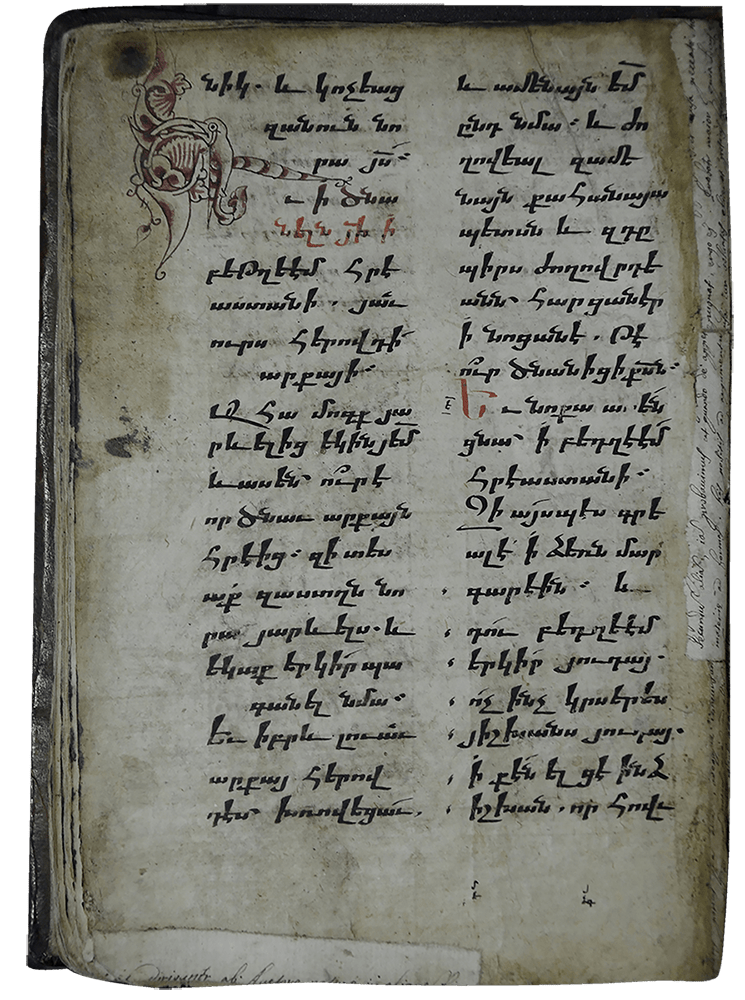

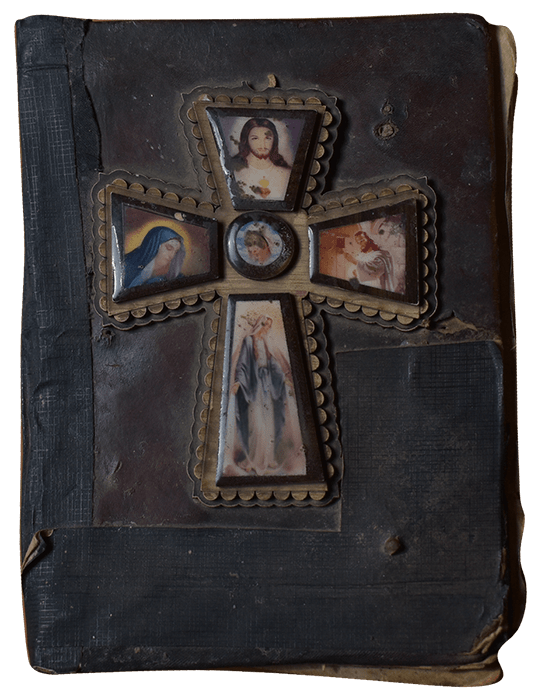

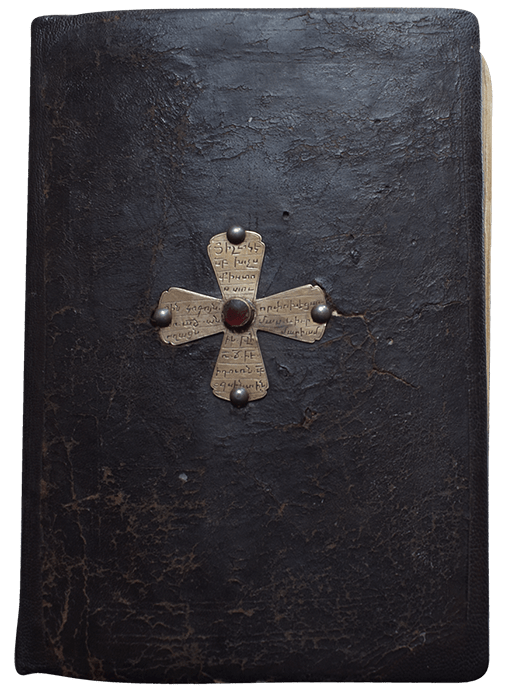

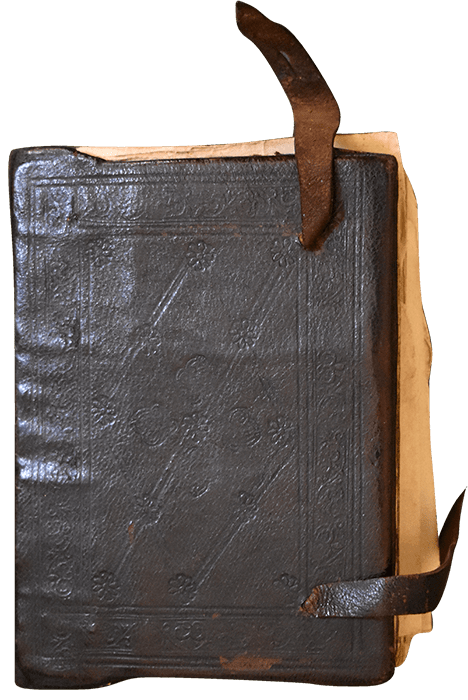

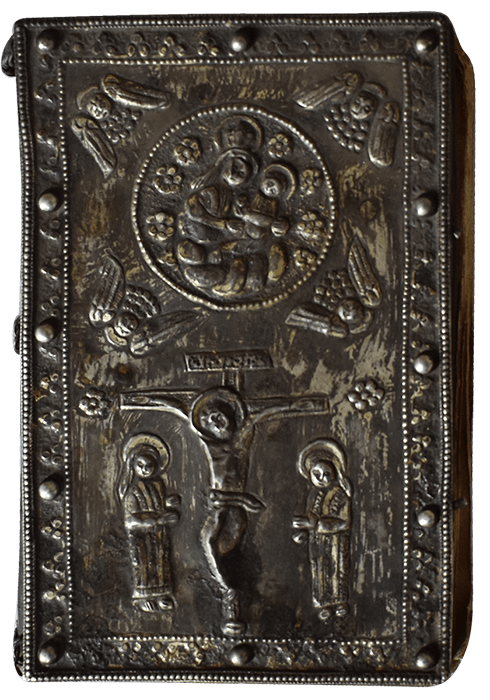

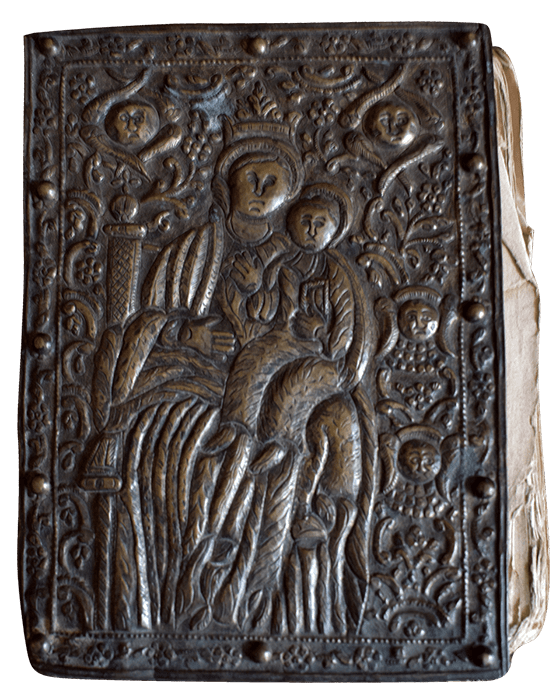

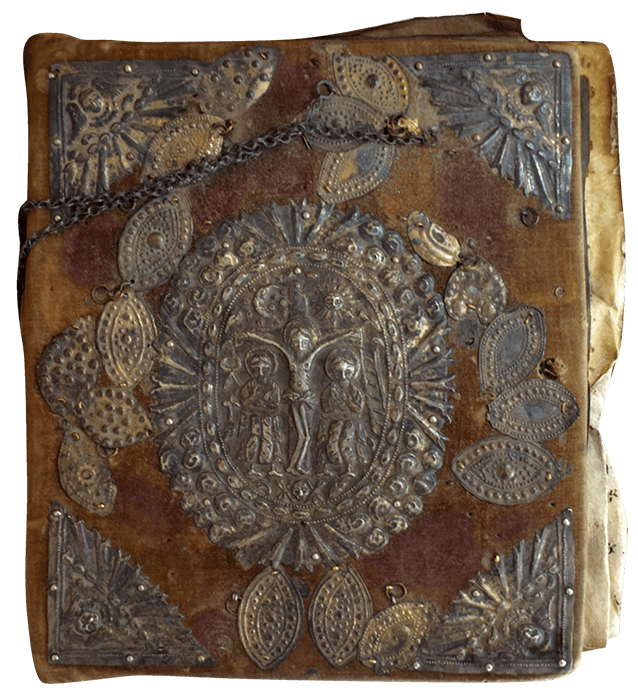

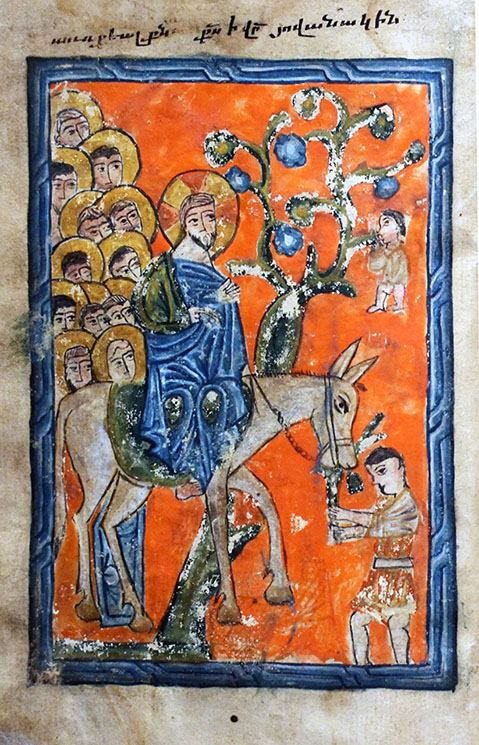

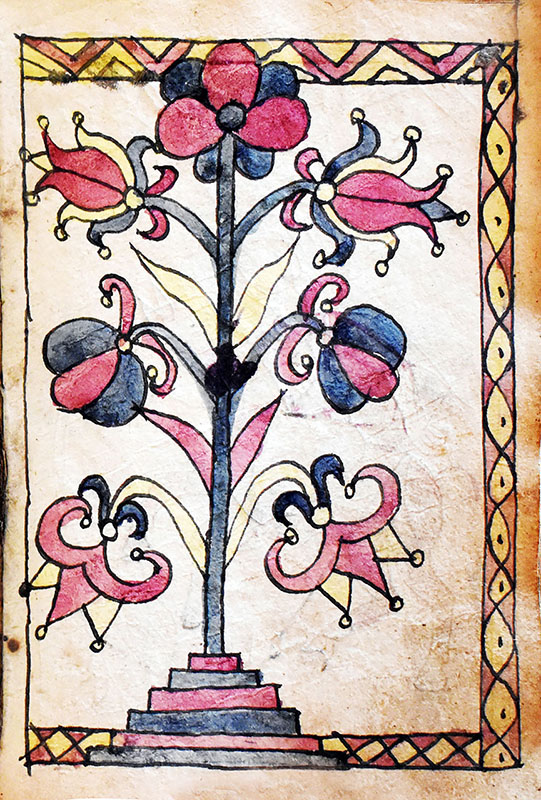

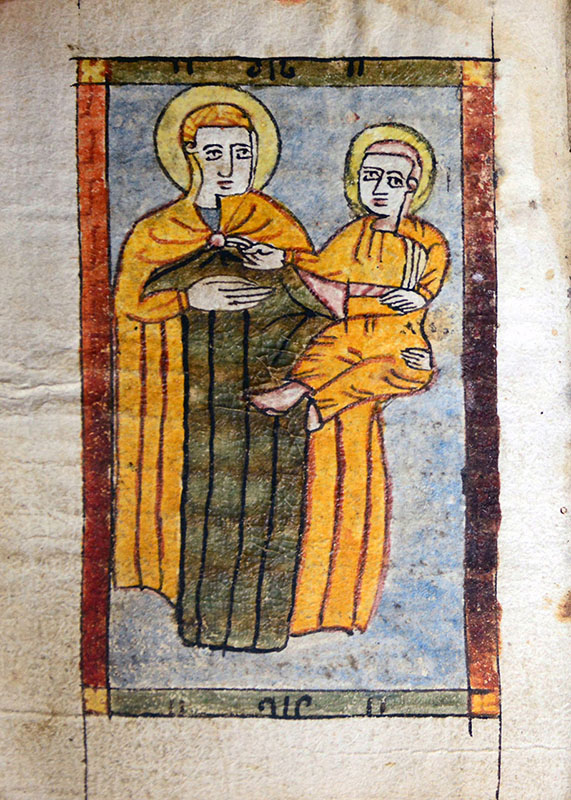

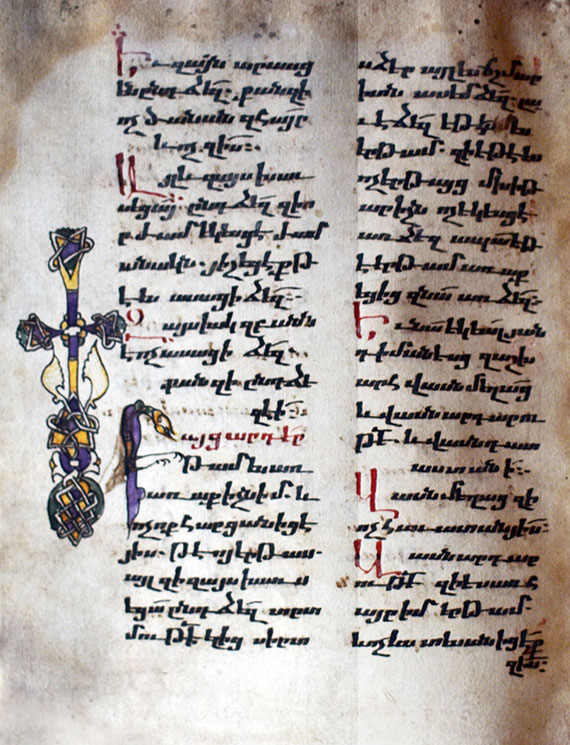

Books are the most common holy objects that are considered to be Home Saints. They can be both printed or handwritten. Some among them are manuscripts that contain miniatures (illustrations) and decorative ornaments created by medieval master illustrators. A holy sanctuary can sometimes have multiple old books, but only one of them is considered being miraculous.

Although not numerous, relics are extremely important objects. Worshipping them is typical to many traditional Christian churches. A relic is a part of a holy person’s a martyr’s bone, or remains of an object that belonged to Jesus Christ or a saint that contains the power of God or that particular saint. When stored in a monastery, even small remains of the True Cross (wood of the cross on which Jesus Christ was crucified) or powerful saints’ bones are viewed by the believers as multipliers of the potential power of the convent and its importance. Only a century ago such relics were carried to epicenters of epidemics to prevent the spread of disease; solemn corteges, processions accompanied with them were effective means to stop hail or make rain; they were famous as being apt to cure critically ill people and even resurrect the dead. During special religious rites, relics were taken out from their storages and made accessible for the crowds to behold and thousands of pilgrims would come to worship them and take communion of their wonder.

Because of some unknown historical reasons such powerful items or at least the decorated boxes or crosses (used as boxes) containing them ended up in private houses. They usually have special inscriptions carved on them. As long as there are people in the family who believe in the power of the relics, they will continue to attract pilgrims.

Crosses, Church utensils and pieces of garments of a priest got their sacred powers from the fact that in their time they have all been blessed and sanctified to be used during church rites and thus carry the mark of holiness. If those items are not found due to some miraculous means, or through visions or dreams, they do not serve as an object of worship (the primary holy object) and are just stored in the same shrine. A blessed member of the family in possession of such items can perform various rituals using them. In some cases, the water that is drunk from those tableware or sacred vessels is considered to be the guarantee of healing.

These objects can become the primary holy object of the Home Saint only in the case if they are found in a miraculous way.

10 Gospels

Most commonly the primary holy objects of the Home Saints are wonder-maker books. Some of those books are medieval handwritten manuscripts that have not only religious but also artistic and historical value.

These books were the main target of digitization during the field research done from 2019 to 2021. Their digital pictures represent the collection created by the research team of the IAE archive named Home Saint Manuscripts (HSM).

The most ancient illustrated manuscript found during the research (HSM №1) is dated to the 9-11th centuries and is one of the oldest samples of Armenian manuscript art.

These manuscripts, as well as most of the holy and miraculous handwritten and printed books, have taken harsh roads and trampled a lot of migratory routes. Some of the manuscripts in the HSM collection have been considered sacred and have once had their chapels in Western Armenia. There are even some that have had the fame of being wonder-makers since the 19th century.

Some of the manuscripts created in the monasteries of Eastern Armenia have ended up in Iran brought by the people deported through the order of Abbas the Great. While written in a monastery of Western Armenia, through various disasters, wars or mass deportations of people the manuscripts have found refuge either in the territories of Western Armenia or in Diaspora communities. Numerous priests became victims of Stalin's repressions, while manuscripts and books kept in churches and monasteries were often thrown into the fire by the Bolsheviks and went up in flames.

Sometimes the priests would hide the highly significant books under the soil to protect them from destruction by enemies or the books sank in water while clergymen were crossing wild rivers trying to rescue them. Some manuscripts that were really found by their new owners through a miracle or a chance were added to the collection of the HSM. Some people found the manuscripts while renovating the newly-bought house, some noticed a chest floating towards them while crossing the river Aras (Arax) on the way of the forceful migrations and preserved the book from inside it, while others were able to hide and guard the books that literally flied out of the fires of Bolsheviks. It is not a surprise that most of these manuscripts have many pages burnt or damaged by water.

Many such stories were written down and audio-recorded during field research of the research team of the IAE archive.

Besides these, there are folk tales of wonders that have happened through the power of these old books. The plots of many of these stories are about the fulfillment of desires: the personified saint of the book appears in the dream of the sick people and promises to cure them if they undergo a journey to the book; the pious mother-in-law would take her childless daughter-in-law to the saint, and soon enough the young woman would have a child; the book was placed under the patient's head and he recovered. There are some tales when the saint punished the people if the book was treated with disrespect or when the book ended up in bad hands.

All of these stories spread fast and are often retold, that is why the living tradition of worshipping holy books continues to maintain.

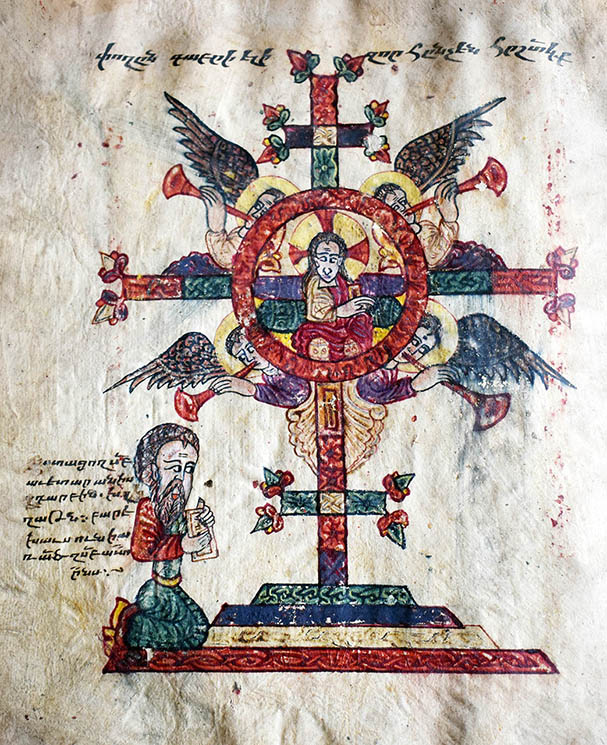

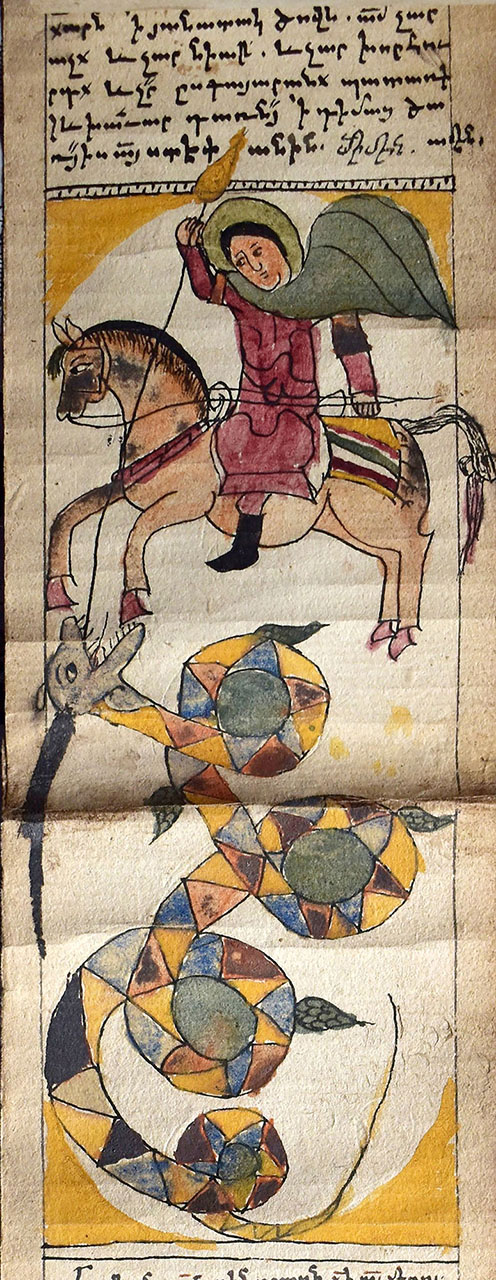

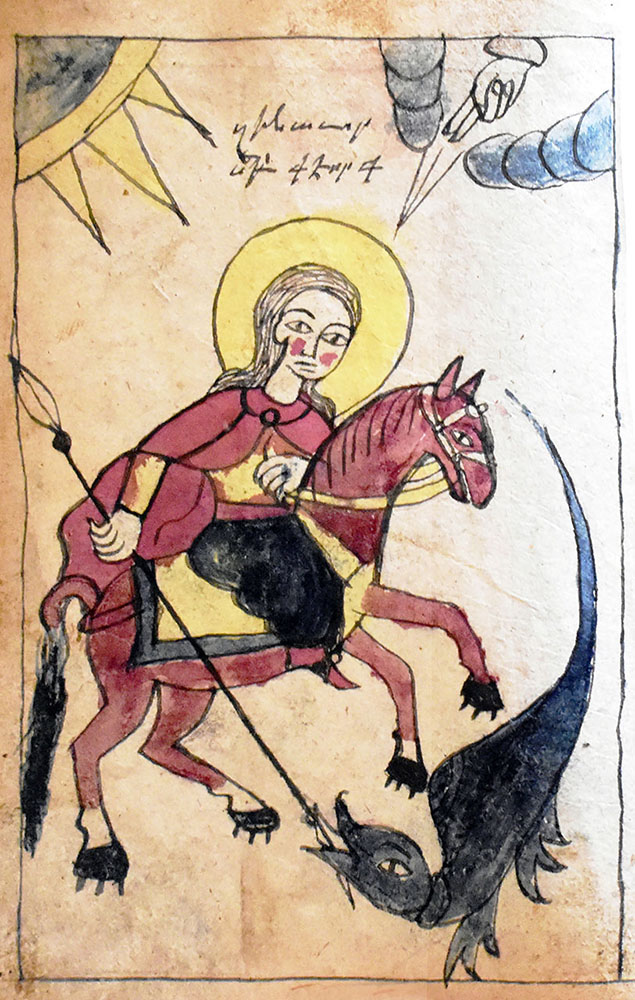

The painter of HSM №6 is Zachariah of Avan, a miniaturist of the 16-17th centuries. In addition to the unique style and colorful palette, his illustrations are characterized by the wide use of Armenian folk mythical plots, due to which the content of Zachariah’s miniatures is also rich.

Wonder-making books help with not every illness. There are books that believers with specific health issues turn to. Some books are known to cure musculoskeletal disorders, others free people from infertility and promote childbearing, the influence of others is related to mental health: they help to get rid of acute fears, fainting, etc. There are rituals performed by the guardians of holy books that also help to understand the causes of illness. All these healings take place without any physical intervention or drugs, and the book’s personified saint becomes the mediator between the patient and God. Thus, the healing requires the presence of faith.

People believe that those books, as well as the holy sanctuaries where they are stored, are like churches and monasteries. In reality, many of these books were indeed stored in functioning convents. There is also information about the fact that even in monasteries and churches, powerful gospels were placed in a separate place, and hundreds of pilgrims went to those monasteries to worship them and seek treatment. In that case, the church can be given a second name, one of which is the name of the miraculous book. One such example is Holy Power Mother of God (Surb Zoravor Astvatsatsin) Church of Yerevan, where until the mid 19th century the Surb Zoravor Gospel was stored.

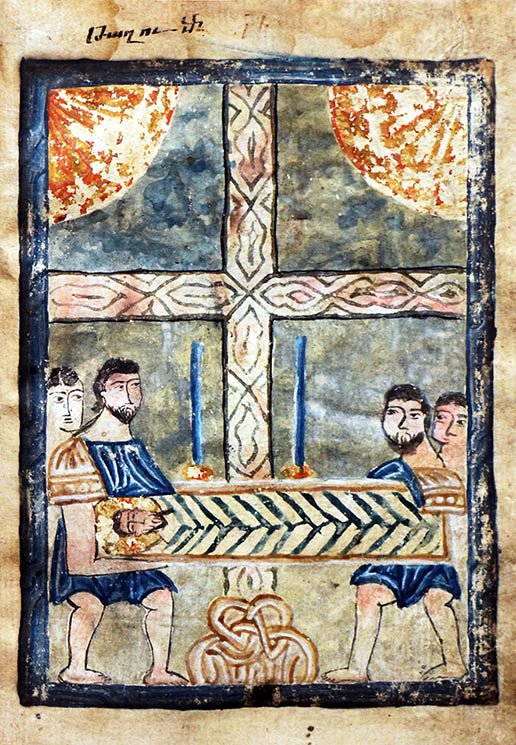

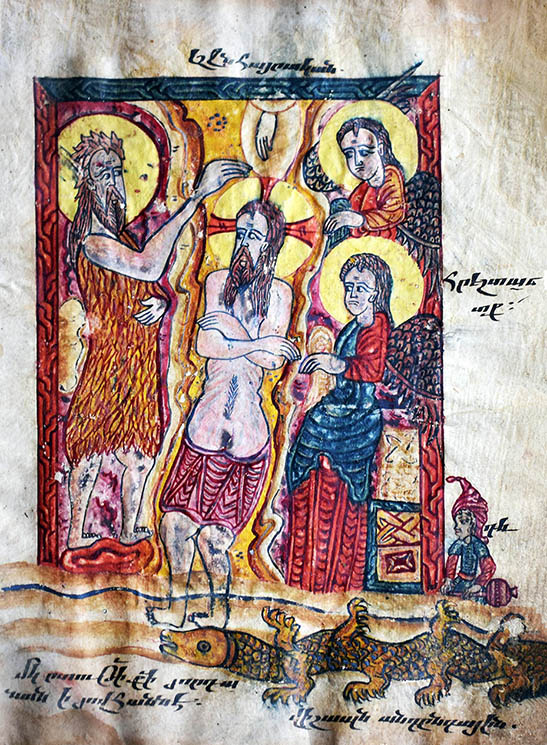

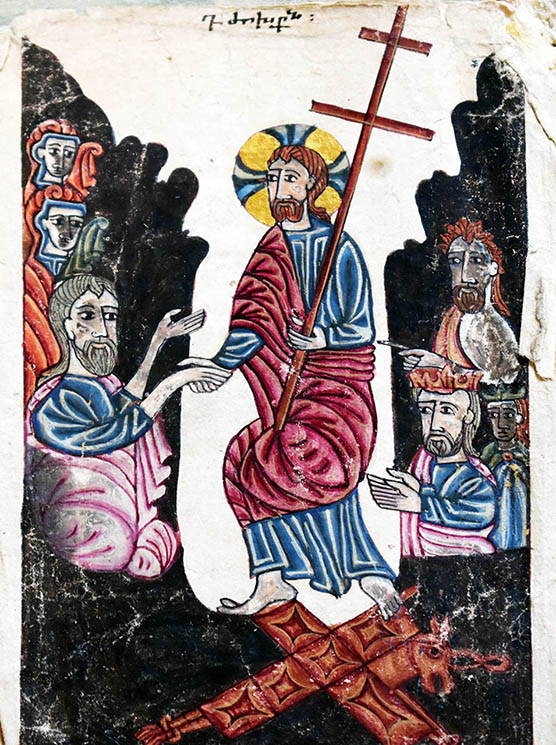

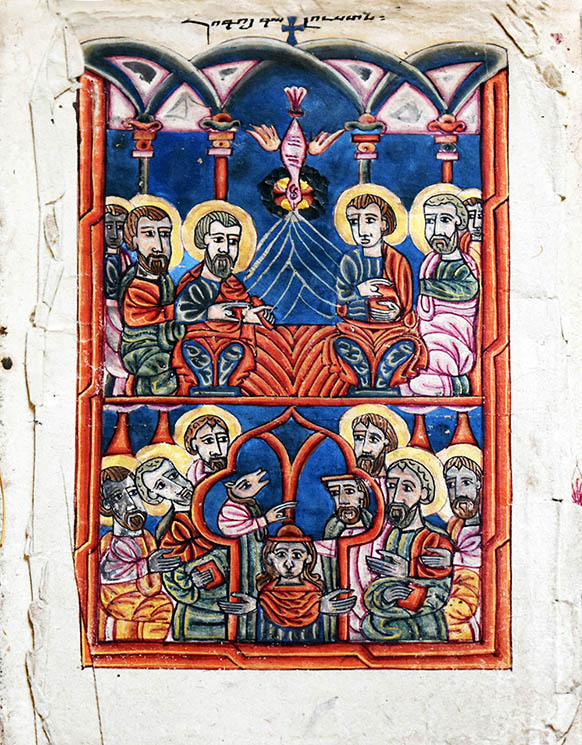

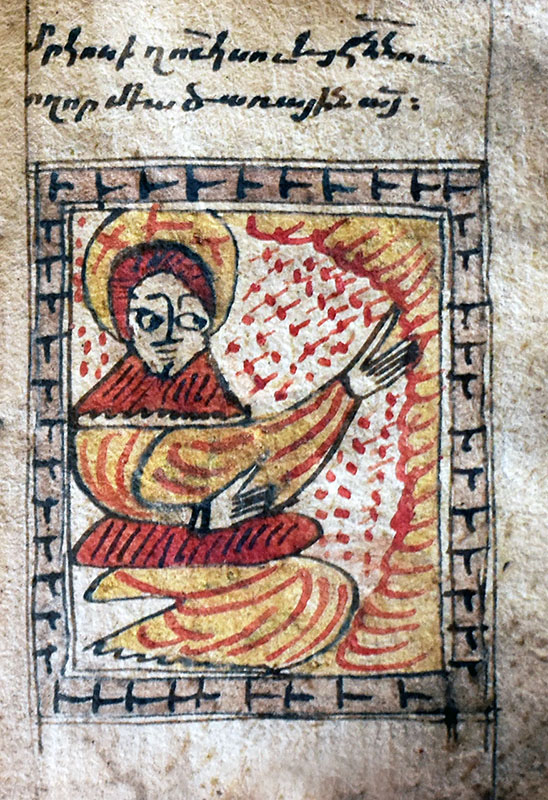

Among the Armenian miniatures on the topic of Pentecost, there are those that have a unique structure and strange characters. The name of the painter of the Gospel (HSM №10, written in 1606 in the Hizan region of Western Armenia, Ketsan village, Monastery of St. Mother of God) has been lost. However, today you have the opportunity to admire the image he created. This ‘Pentecost’ breaks all the rules of that miniature type. Here the apostles are depicted not in the upper part of the image divided vertically into two parts, but equally in both parts. The six apostles depicted on the top witness Jesus descending as the Holy Spirit, while a completely different scene is depicted between the three apostles drawn below: a Dog-head blessing a person without a halo and underneath one more person with open, outstretched palms. The Dog-head, especially in the miniature of Vaspurakan province, is Saint Christopher. Beginning from the 13th century, his sermon and metamorphosis have been traditionally included in the Armenian miniatures of Pentecost. The man with outstretched palms who is paralleled with the spirit of the dead in the miniatures of the same topic most likely embodies the Eastern parable, which states that no one can take anything with him to the other world.

One more unique graphic tradition of late medieval Armenian miniatures is the scene of the Final Judgment, where Jesus sits on a Four-faced chair (The Throne in Heaven) surrounded by symbols of St. Evangelists. At the bottom of the illustration good and evil deeds are weighed on scales. The miniaturist also added the main patrons - Holy Mother of God and St. John the Baptist, who stand on the top of the illustration on both sides of Jesus; while the devils are trying to interfere with the scales.

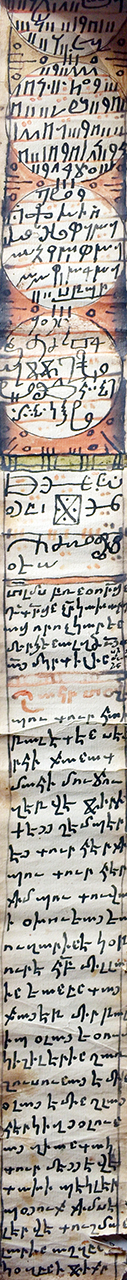

A magic scroll (hmayil) is a collection of specific biblical texts, protective and redeeming prayers written on a long strip of parchment or paper. Scrolls were written by order of an individual and had the aim of protecting that person from various misfortunes, diseases, and devils until the person's death. According to an old custom, they should not be opened or read except in extreme cases when the owner of the scroll was on the verge of death. Only then would the priest open and read the magic scroll. However, when the original owner died, the same scroll package could be used by another person who simply erased the name of the previous owner and wrote his own, expecting the patronage of all the prayers and saints in the scroll.

After this tradition was forgotten, ancient, especially handwritten and illuminated scrolls began to play the same role as the Holy Script manuscripts. They were stored in sanctuaries or in a special place inside the house and used for healing rituals. The high regard for these has not diminished even today.

As the main function of these scrolls was charming and magical defense, unique charms written with special magic characters (an alphabet or symbols) are often found in them. Many medieval Armenian scribes were masters of such writings. At present we are unable to decipher these writings, although they probably belong to the same tradition as similar Assyrian, Arabian, Hebrew and Ethiopian writings.

Besides gospels and magic scrolls, there are other sacred books: St. Narek (the Book of Lamentations, the prayer book of Saint Gregory of Narek, all its samples are printed), as well as several books on astrology (Akhtark’) and Books of Friday (Urbatagirk).

Akhtark is simultaneously a collection of calendars and of astronomical and to some extent magical texts and tables, it also plays the role of protection.

The Book of Friday is mainly a collection of healing prayers, as Friday was considered the most favorable day of the week for healing. It is known that The Book of Friday was the first printed book in Armenian (Venice, 1512), which also points out the importance of the book’s content. Nevertheless, all the Books of Friday which are considered sacred books found by the research team of the IAE archive are manuscripts, and their content partially coincides with the content of magic scrolls. Both in the scrolls and the Books of Friday, there are numerous illustrations of patron saints.

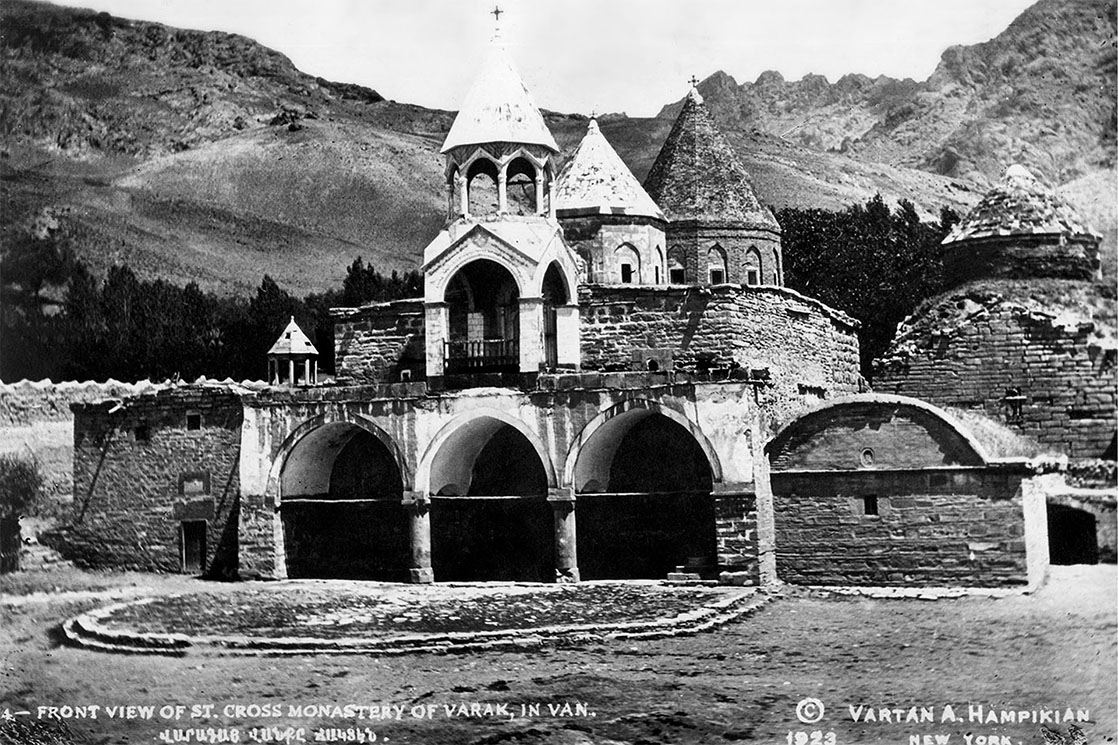

The manuscripts digitized during the 2019-2021 field research of the team of the IAE Archive are copied and illuminated in famous scriptoria-centers of historical Armenia. In particular, the manuscripts discovered during the study are created in Hagphat Monastery (currently a functioning monastery in the Lori region of Armenia); Holy Savior Cathedral of New Julfa (currently a functioning cathedral in Isfahan, Iran); Saint Karapet Monastery of Aprakunis; Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Akhtamar; (old) Varagavank; the Church of the Holy Archangels, Bayburd, Southern Tayk; Holy mother of God in Ketsan, Hizan; Saint John of Mahmoudank (last five are currently in the territory of Turkey). Some of the structures mentioned above are completely destroyed.

Such a case is the Saint Karapet Monastery of Aprakunis historically located in Aprakunis village of the Yernjak canton, Syunik province of Greater Armenia which was founded in 1381 by Crimean monk Malakia. There was a university-level school at that convent under the rabbinical leadership of Hovhan Vorotnetsi. This territory is now located in the Republic of Azerbaijan, in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. In 2004 the monastery was completely destroyed by the orders of Azerbaijani leadership.

SUMMARY

The Holy Saint Manuscripts digital collection is the result of field research done by the research team of the IAE archive. The archive includes photos of codices which are considered to possess holy powers and usually remain inaccessible to the general public.

Worshipping holy scripts is still widespread among the Armenian people. People undertake pilgrimages to holy sanctuaries dedicated to sacred books where they find peace of mind, are cured of a number of diseases, find their protection and the solution to their problems.

Many oral tales have been preserved about the historical paths of holy books, and stories on miracles have arisen around the marvels performed by their personified saints.

Some of the miraculous books are valuable ancient manuscripts, and the illustrations found in them have undeniable artistic value. Since many of these manuscripts were written in monasteries or churches which are ruined, or extinguished and lost today, they are part of national memory and have great historical significance.

HOME SAINT MANUSCRIPTS

Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of NAS RA

Lilit Simonyan, Hayk Hakobyan, Karen Hovhannisyan

Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation

Text by Lilit Simonyan, Hayk Hakobyan, Karen Hovhannisyan

Music by Lilit Simonyan

Photographs:

All rights of photographs of field works and manuscripts used in the Project belong to the

Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of NAS RA.

Photograps of Armenian monasteries:

Abrakunis St. Karapet monastery. old photograph by Artak Vardanyan, 1986,

new photograph by Stiven Sim, 2005.

Old Varag monastery. archival and new photographs by Jirayr Salmastetsi, 2019.

St. Amenaprkich monastery of Julfa. photograph by Samvel Karapetyan, 2009.

St. Archangels monastery of Baberd. photograph by Samvel Karapetyan, 2007.

Aghtamar St. Cross monastery. photograph by Hayk Hakobyan.

Haghpat monastery. photograph by Tigran Apikyan.

Special thanks to the Research on Armenian Architecture Fund (RAA)

and Artak Vardanyan for providing photographs.

https://raa-am.org/պատկերասրահ/

Creation of the el. exhibition: Tigran APIKYAN